Trigger warning: Mention of miscarriage, pregnancy loss.

I spend a lot of my time extolling the virtues of a biology everywhere mindset.

I wrote a book on it after all – about how we experience biology as part of our daily lives. That when we start seeing #biologyeverywhere, it becomes less intimidating and more accessible.

In fact, the value of a biology everywhere mindset and the importance of having one for the health and welfare of society factors prominently in my TED-Talk. I also talk about how having that biology everywhere mindset was helpful getting through my son’s first few days of life, when we were managing jaundice caused by ABO incompatibility.

And, at the risk of sounding like a hypocrite, it IS important for the health and welfare of society AND it can be helpful with the more painful realities of biology in our lives– but there are limitations too.

I found out I was pregnant just after the new year in 2021. After 2020 and the COVID-19 pandemic – plus a personally difficult 2019 — a positive pregnancy test right after the new year was a sign of hope and new beginnings.

As I made the requisite phone calls that accompany early pregnancy to various medical providers, setting up appointments, and such, I pondered how interesting it would be to teach genetics that semester while being pregnant. I teach introductory genetics each spring at the University of Colorado Boulder to students with aspirations in medical professions.

To be talking about inheritance in its many flavors, all while wondering what the child inherited from me and my husband.

Little did I know that I would, in fact, be teaching about biology in my own life … but not in the way I expected.

A few weeks into the semester, right in the middle of the unit on Mendelian inheritance, was when I first passed blood.

I called my provider. She wasn’t concerned – it can be normal after all. However, I was worried and asked for an ultrasound. My provider agreed, and I scheduled to go in the following week – just to be sure everything was alright.

Meanwhile, that week in class, we discussed meiosis and chromosomal abnormalities. Considering that sometimes, chromosomes don’t go where they are supposed to, leading to everything from Down Syndrome to miscarriage.

How the likelihood of miscarriage increases as a woman ages because of how egg cells divide. Division starts when a woman is a fetus in her mother’s womb, then arrests until ovulation (when meiosis 1 completes) and eventually fertilization (when meiosis 2 completes).

The putative egg cell sits in suspended animation for decades. That’s a long time to pause – and that’s why as a woman ages, the quality of her eggs declines. As egg quality declines, the probability of chromosomal abnormalities increases – and the more likely she is to have a child with Down Syndrome or miscarry.

The day after teaching about meiosis and miscarriage, I was scheduled for my ultrasound. I repeated over and over to myself that everything was fine. I hadn’t passed any more blood and was still enjoying the hallmark symptoms of early pregnancy.

The ultrasound room had a large monitor where I (and my husband) could see what the technician saw. I had a good sense of what to look for – both from being pregnant before, seeing so many ultrasound birth announcements, and having a degree in developmental biology.

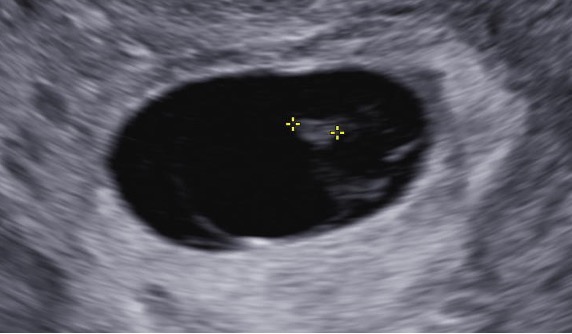

So, I picked out the gestational sac immediately (cover image). But I didn’t see anything else. Neither did the ultrasound technician, who after looking for what seemed like an eternity, uttered the sentence that no one ever wants to hear: “I’m sorry, I can’t find a heartbeat.”

I was diagnosed with what’s called a missed or incomplete miscarriage.

Incomplete miscarriages occur when conception and implantation (when the baby connects with mom’s uterus) occur as normal, but development arrests – often due to chromosomal abnormalities. And the irony of the fact that I just taught that content to my students was not lost on me.

Since the gestational sac was still intact, my body was still full of pregnancy hormones – which is why I still felt pregnant. So, while still feeling nauseous and with sore breasts, I had to make decisions about how to terminate a wanted pregnancy. And come to grips with the idea that the baby I had been speaking to in my mind for weeks was gone.

Understanding the biology of miscarriage doesn’t negate the intense grief of losing a child

It might be tempting to think that because I understood the biology of what happened that my grief was less. Because #biologyeverywhere, right?

Nope.

The only thing I will say helped was knowing I couldn’t have stopped it.

Chromosomal abnormalities meant the pregnancy was doomed at conception.

If it had continued, my baby would have suffered – and like any mother, I will do anything to save my child from suffering.

It didn’t matter that I exercised, or gave into intense pickle cravings, or binge-watched Bridgerton when the nausea and fatigue were too much.

Sexual reproduction is an imperfect process – and meiotic defects happen.

So, while my biology everywhere mindset did bring some peace – it didn’t alter my grief.

Grief for a child no one really knew but me.

How much of a mother’s grief (or anyone’s grief) after miscarriage is biological versus spiritual?

How much of it is related to the deep-rooted instincts to love and nurture a child, even before they come Earthside?

And how much is the spiritual knowledge that there was someone there – a living entity separate from myself who did exist within me, if only for a short time?

That’s a biological fact – we conceived, and the child began to develop. Something went wrong, and the baby died – also a biological fact.

But feeling a connection to whomever that child was or would have been? How much of that connection can be explained by biology?

Which brings me to the take-home message of my story.

Biology explains many things in our lives – that’s the whole point of the #biologyeverywhere mindset after all. But what about those things we can’t explain with biology…or can’t explain yet?

There is a real need for research into the biology and psychology of pregnancy loss. It’s shocking to me that pregnancy loss impacts many people – and yet we know so little about what these losses mean to people and how to best support bereaved parents.

Dr. Kenneth Doka, an expert on the psychology of grief, refers to child loss as “disenfranchised grief.” It’s a type of loss typically not acknowledged by and/or minimized by society – in this case, because it’s a “hidden” type of loss.

The biology of why miscarriage happens doesn’t explain the genuine grief both I and others face with the loss of a child. Some things are more than the sum of their biological parts and fall into the realm of the mysterious and spiritual – and illustrate the limits of science.

The day before I found out my baby was gone, I shared the 1 in 4 statistic with my students. Not that 25% of women have a miscarriage – that 25% of all pregnancies end in loss.

Someone you know has had a miscarriage.

Not only that, someone you know is grieving a lost baby.

Mothers are some of the strongest people you’ll ever meet – because so many of us gave birth to angels and still found a way forward.

How do we get more research on the biology and psychology of pregnancy loss?

It starts with acknowledging that it happens a lot.

That, as more people delay childbearing to their later years, those numbers are going to increase. There are calls for starting the discussion with young women of the balancing act of getting an education and/or career started and having children prior before the miscarriage risk becomes too great.

I shared my story today to bring attention to the fact that the profound grief felt by bereaved mothers – and their families- is real.

That by acknowledging the experience of bereaved parents, even when it hurts, gets the ball rolling for more advocacy and research.

What will you do with your newfound knowledge of miscarriage?

Want more information? Here is a comprehensive list of resources for bereaved parents, family members, and medical professionals.